This eFLYER was developed in HTML for viewing with Microsoft Internet Explorer while connected to the Internet: View Online.

To ensure delivery to your inbox, please add eFLYER@barnstormers.com to your address book or list of approved senders. |

|

ISSUE

188 - September 2011

Over 9,000 Total Ads Listed

1,000+ NEW Ads Per Week |

| Sometimes The Obvious Isn’t |

By David Rose, Contributing

Editor

San Diego, California |

In the early ‘60’s and I had been racing cars for almost three years and it finally came to me that this was no way to enjoy life. The ‘50’s and early ‘60’s happened to be the most dangerous periods for drivers in that, for the most part, the drivers enjoyed only the most rudimentary safety precautions. Some cars had safety belts and roll bars, but the regulations allowed for the flimsiest of excuses in that regard. Passing tech inspection was often done with a smile and a promise. In the early ‘60’s and I had been racing cars for almost three years and it finally came to me that this was no way to enjoy life. The ‘50’s and early ‘60’s happened to be the most dangerous periods for drivers in that, for the most part, the drivers enjoyed only the most rudimentary safety precautions. Some cars had safety belts and roll bars, but the regulations allowed for the flimsiest of excuses in that regard. Passing tech inspection was often done with a smile and a promise.

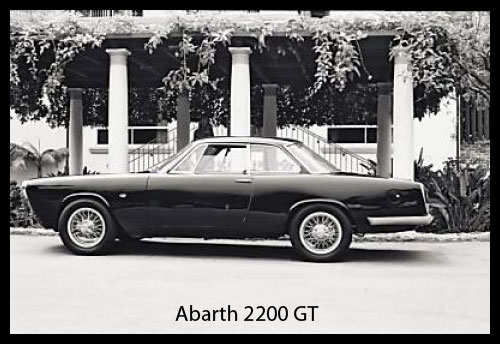

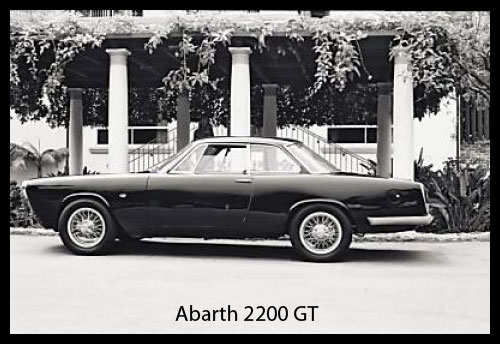

Impact absorbing crush structures were high tech stuff still decades in the future. The simple things like run off areas were never much considered. Hay bales lining the street were state of the art for course safety in those days. Trained crash responders? Doctors in the pits? Life flight helicopter evacuation? Triple layer Nomex fire protective driving suits? Non existent. Not only that, but politics, intrigue and downright skullduggery were rampant among the organizers, owners and officials. It all combined to make me realize this was not for me. Oh it was great fun to drive the cars, and I had just been offered a career securing seat by a very competitive owner, but the hard work, lack of money and frustrations colluded to send me flying back to flying. Besides, with so little law enforcement on the open roads in those days, I could drive my Abarth 2200 GT to its fullest potential almost at will. |

|

Once I made the decision, the rest was amazingly simple. A call to the Air Force Reserve Records Center in Denver got me recalled to active duty, with, at my insistence, a directive duty assignment to day fighter 104’s. Now we’re talkin’!

The car racing had been an unscheduled diversion from my intended flying career. My plan had always been to somehow wrangle my way into 104’s, but I had been offered a chance to race Ferraris, and without much thought had taken it. (The Factory connections made in those years would stand me in good stead for a dealership years later) But I’m back on course now as I sign in to the 476th TAC Fighter Squadron at George AFB, Victoville, California. Thus began my month long checkout in what I had always conside red to be THE ultimate pilots airplane. Said checkout was accomplished under the watchful eyes of squadron check airmen like Ray Holt and Tom Delashaw. All my career I had been fortunate to have the best instructors and my transition into the 104 was to be no exception. These two accomplished airmen guided me through transition, gunnery, and ACM (air combat maneuvering, dog fighting). It was a happy day when they presented me my own set of ‘spurs’ * red to be THE ultimate pilots airplane. Said checkout was accomplished under the watchful eyes of squadron check airmen like Ray Holt and Tom Delashaw. All my career I had been fortunate to have the best instructors and my transition into the 104 was to be no exception. These two accomplished airmen guided me through transition, gunnery, and ACM (air combat maneuvering, dog fighting). It was a happy day when they presented me my own set of ‘spurs’ * |

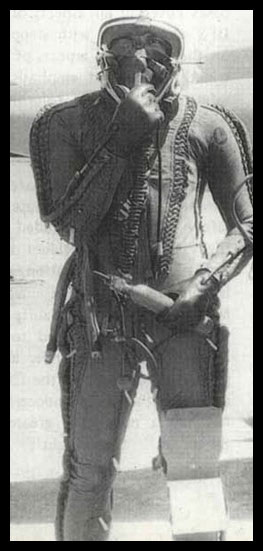

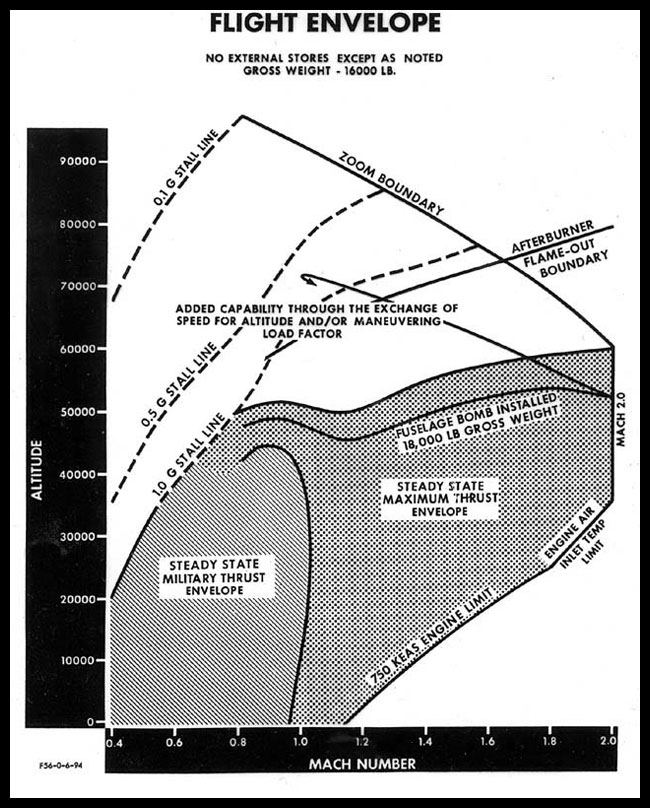

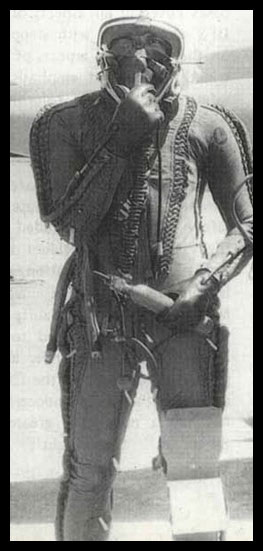

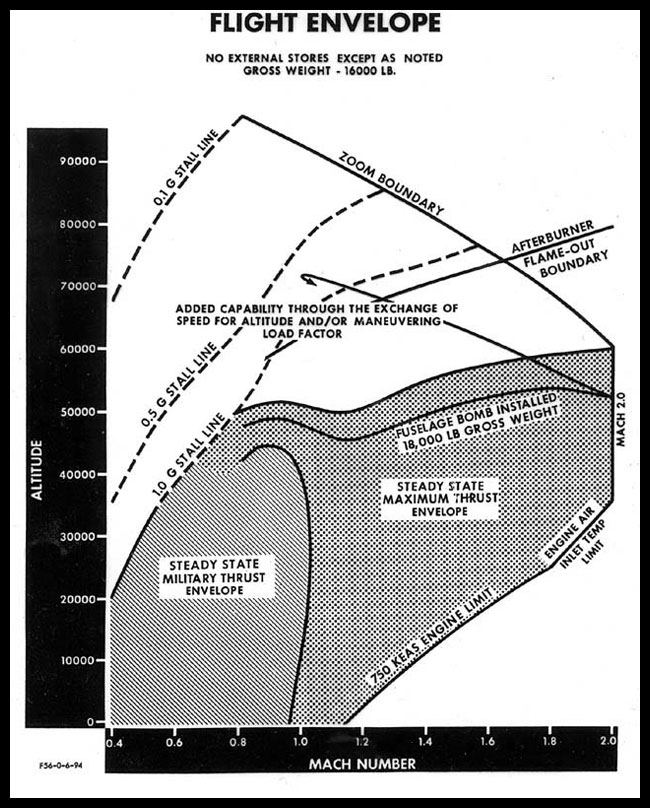

Once fully qualified and “combat ready” in the airplane, I was eligible to fly a ‘Zoom Climb’ mission. The checkout syllabus had it as option and of course I wanted it. But first I would need a full pressure suit; problem was the Air Force had ceased issuing them to squadron pilots several years before. Fortunately there were several of them around the squadron and I was able to borrow one for the flight.

They had a bird cleaned up for me, removing tip tanks, bomb racks and the refueling probe and I was ready to go. Tom and Ray briefed me on what to expect as I suited up that morning and I listened intently. It all sounded simple enough; climb to the ‘trop’, level off, accelerate to over mach 2, pull smartly up into an 85 degree climb attitude and hang on; at 80 or 90,000 feet let the nose fall through the horizon and come on down. Great stuff. In retrospect, the guys seem to be in awfully good humor as they aided me in lacing up the suit. They laughed and joked as they finally got me trussed up and checked over. As it turned out, their good humor had much to do with the one little detail they left out of my otherwise thorough briefing. |

Strapped in and fired up, I taxied out without delay; the fuel load in a clean configuration doesn’t leave a lot of time for lollygagging about. Still coming to grips with the odd feel of switches and control through the thick gloves of the pressure suit, I blast off and contact Edwards for permission to enter the SOA. (Special Operations Area) This is the enormous restricted area controlled by Edwards AFB within which every fantastic test flight you have ever heard off probably took place. Today, for a few minutes anyway, a part of it would be mine. Cleared in, I lit the ‘burner’ and in just a minute or two was leveling off at 33,000 feet. A minute and nineteen seconds are all this fantastic bird requires to accelerate from .9 to Mach 2, and at a little over Mach 2 I’m pulling up into the 85 degree angle predicted to take me up to a hundred thousand feet or so. Strapped in and fired up, I taxied out without delay; the fuel load in a clean configuration doesn’t leave a lot of time for lollygagging about. Still coming to grips with the odd feel of switches and control through the thick gloves of the pressure suit, I blast off and contact Edwards for permission to enter the SOA. (Special Operations Area) This is the enormous restricted area controlled by Edwards AFB within which every fantastic test flight you have ever heard off probably took place. Today, for a few minutes anyway, a part of it would be mine. Cleared in, I lit the ‘burner’ and in just a minute or two was leveling off at 33,000 feet. A minute and nineteen seconds are all this fantastic bird requires to accelerate from .9 to Mach 2, and at a little over Mach 2 I’m pulling up into the 85 degree angle predicted to take me up to a hundred thousand feet or so.

|

|

With the nose pitched up so high, I find myself flat on my back looking side to side, trying to maintain what, to the pilot, should look to be an 85 degree climb angle. The actual aircraft attitude at this point is around 70 degrees and by the time I’ve established the climb I’m already topping 50,000 feet. A moment later we’re past 60,000 and I’m watching for the sky to darken as we pass 70,000. 80,000 passes a moment later. The sky has perceptively darkened now and I‘m just beginning to think about lowering the nose, when it all seems to go horribly wrong.

Now ‘gimmy’ a break here; I’m brand new to this bird and pretty pumped about finally getting to fly it; plus! I’ve had my feet firmly on the ground for nearly three years, so what is obviously coming next just hadn’t occurred to me. With the suddenness of a thunder clap, my suit inflates and the cockpit fills with a misty vapor. It takes a second for me to restart my heart and realize that climbing up through 85,000, the engine has simply run out of air and shut down. With no engine bleed air I loose pressurization and the suit has taken over by inflating and providing breathing oxygen under pressure. OK.

Of course I knew there was the possibility I’d lose the engine; that pressurization would be lost and that the suit would inflate. What you don’t think about is that when the suit inflates, it fills those little tubes running along your arms and legs with high pressure air which straightens them right out. And here I sit, arms and legs outstretched, my right hand now off the stick and my left off the throttle. So why am I now laughing out loud ? Because Tom and Ray knew the engine would blow out, and the picture of me, hunched over in the cockpit with my arms and legs rounded out in front of me, eyes as big as saucers, and still climbing like a rocket is what had danced in their minds as they prepared me for the flight. I made a note to get them back, someday.

I soon discovered that it was not impossible to bend my arms and legs and get back on the controls. But with the engine dead the throttle was useless and the air was so thin it render the stick a meaningless protuberance in the cockpit. With no control over anything for the foreseeable future, I relaxed to enjoy the ride. At what Edwards would later confirm as “over a hundred thousand feet” (perhaps generously so), the bird had reached it apex and coasted over the top. Still in an insane nose high attitude, the thing was now descending and accelerating tail first. There was little to do but marvel at the ride down. Take a moment to understand the situation; this is going to take a long time. We’re falling at maybe 10,000 feet per minute and we have something like a hundred thousand feet to go. Two or three minutes go by before the nose points down. Five or six minutes pass as I fall toward the desert. Five or six minutes! It seemed a lot longer then, but finally air has entered the intakes and the engine has slowly come up to twenty or thirty percent. From here it’s a simply a matter to wait for the dense air down around twenty five thousand, bring the throttle around the horn and light off. The engine comes to life as well as ever and we head back to George. I’m still fat on fuel but the pressure suit and the desire to rag on the two architects of my experience take me to the pattern and landing. As I reach the pits and shut down the crew chief is grinning as he runs up the ladder. He knows the plot and asks if I’ll need to have the suit cleaned out. “Very funny” I retort. I suppose most pilots plan for the fact that the engine will quit, that they’ll loose pressurization, that the suit will suddenly inflate and that their arms and legs will shoot out; but I for one wouldn’t trade the surprise and joy of the way that flight went for anything. Sure it’s obvious that the engine would give up when it ran out of air, but sometimes passion and joy obscure the obvious. I soon discovered that it was not impossible to bend my arms and legs and get back on the controls. But with the engine dead the throttle was useless and the air was so thin it render the stick a meaningless protuberance in the cockpit. With no control over anything for the foreseeable future, I relaxed to enjoy the ride. At what Edwards would later confirm as “over a hundred thousand feet” (perhaps generously so), the bird had reached it apex and coasted over the top. Still in an insane nose high attitude, the thing was now descending and accelerating tail first. There was little to do but marvel at the ride down. Take a moment to understand the situation; this is going to take a long time. We’re falling at maybe 10,000 feet per minute and we have something like a hundred thousand feet to go. Two or three minutes go by before the nose points down. Five or six minutes pass as I fall toward the desert. Five or six minutes! It seemed a lot longer then, but finally air has entered the intakes and the engine has slowly come up to twenty or thirty percent. From here it’s a simply a matter to wait for the dense air down around twenty five thousand, bring the throttle around the horn and light off. The engine comes to life as well as ever and we head back to George. I’m still fat on fuel but the pressure suit and the desire to rag on the two architects of my experience take me to the pattern and landing. As I reach the pits and shut down the crew chief is grinning as he runs up the ladder. He knows the plot and asks if I’ll need to have the suit cleaned out. “Very funny” I retort. I suppose most pilots plan for the fact that the engine will quit, that they’ll loose pressurization, that the suit will suddenly inflate and that their arms and legs will shoot out; but I for one wouldn’t trade the surprise and joy of the way that flight went for anything. Sure it’s obvious that the engine would give up when it ran out of air, but sometimes passion and joy obscure the obvious.

Such was the nature of my years in the greatest bird I will ever have the experience to fly (I think) and such was the nature of my time at George. Day Fighter 104’s. What more could you ask ?

For some perspective on my flight – Link to George Marrett’s article in the Air & Space magazine to see how they flew this “Zoom Flight” out of the test pilots school at Edwards –

http://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/starfighter.html. You’ll discover they did things a little differently over there – the planning, caution and professionalism with which they conducted similar flights show how cavalier us ‘ol squadron pilots really are.

And – in case you might be interested in my latest folly – read about the RP-4 in this months Mechanics Illustrated – on the news stands now - as they say. |

| * Spurs. 104 pilots wore metal covers on the heals of their flight boots which they would ‘hook’ on to cables running out of the ejection seat. If they ejected, the retract mechanisms within the seat would pull their feet back in order to clear the canopy rail as the seat left the aircraft. They were known as ‘spurs’. It was not unusual for 104 jocks to wear them out on the flight line of a strange Base to advertise that 104’s were in the area and that they were it’s pilots. |

|

| |

Visit www.barnstormers.com -

post an ad to be viewed by over 1,000,000 visitors per month.

Over 15 years bringing more online buyers and sellers together

than any other aviation marketplace.

Don't just advertise. Get RESULTS with Barnstormers.com. Check

out the Testimonials |

Copyright © 2007-2011

All rights reserved.

|

| UNSUBSCRIBE

INSTRUCTIONS: If you no longer wish to receive this eFLYER, unsubscribe

here or mail a written request to the attention of: eFLYER

Editor BARNSTORMERS, INC. 312 West Fourth Street, Carson City,

NV 89703. NOTE: If you registered for one or more hangar accounts

on barnstormers.com, you must opt out of all of them so the eFLYER

mailings will be fully discontinued. |

|

In the early ‘60’s and I had been racing cars for almost three years and it finally came to me that this was no way to enjoy life. The ‘50’s and early ‘60’s happened to be the most dangerous periods for drivers in that, for the most part, the drivers enjoyed only the most rudimentary safety precautions. Some cars had safety belts and roll bars, but the regulations allowed for the flimsiest of excuses in that regard. Passing tech inspection was often done with a smile and a promise.

In the early ‘60’s and I had been racing cars for almost three years and it finally came to me that this was no way to enjoy life. The ‘50’s and early ‘60’s happened to be the most dangerous periods for drivers in that, for the most part, the drivers enjoyed only the most rudimentary safety precautions. Some cars had safety belts and roll bars, but the regulations allowed for the flimsiest of excuses in that regard. Passing tech inspection was often done with a smile and a promise.

red to be THE ultimate pilots airplane. Said checkout was accomplished under the watchful eyes of squadron check airmen like Ray Holt and Tom Delashaw. All my career I had been fortunate to have the best instructors and my transition into the 104 was to be no exception. These two accomplished airmen guided me through transition, gunnery, and ACM (air combat maneuvering, dog fighting). It was a happy day when they presented me my own set of ‘spurs’ *

red to be THE ultimate pilots airplane. Said checkout was accomplished under the watchful eyes of squadron check airmen like Ray Holt and Tom Delashaw. All my career I had been fortunate to have the best instructors and my transition into the 104 was to be no exception. These two accomplished airmen guided me through transition, gunnery, and ACM (air combat maneuvering, dog fighting). It was a happy day when they presented me my own set of ‘spurs’ *

Strapped in and fired up, I taxied out without delay; the fuel load in a clean configuration doesn’t leave a lot of time for lollygagging about. Still coming to grips with the odd feel of switches and control through the thick gloves of the pressure suit, I blast off and contact Edwards for permission to enter the SOA. (Special Operations Area) This is the enormous restricted area controlled by Edwards AFB within which every fantastic test flight you have ever heard off probably took place. Today, for a few minutes anyway, a part of it would be mine. Cleared in, I lit the ‘burner’ and in just a minute or two was leveling off at 33,000 feet. A minute and nineteen seconds are all this fantastic bird requires to accelerate from .9 to Mach 2, and at a little over Mach 2 I’m pulling up into the 85 degree angle predicted to take me up to a hundred thousand feet or so.

Strapped in and fired up, I taxied out without delay; the fuel load in a clean configuration doesn’t leave a lot of time for lollygagging about. Still coming to grips with the odd feel of switches and control through the thick gloves of the pressure suit, I blast off and contact Edwards for permission to enter the SOA. (Special Operations Area) This is the enormous restricted area controlled by Edwards AFB within which every fantastic test flight you have ever heard off probably took place. Today, for a few minutes anyway, a part of it would be mine. Cleared in, I lit the ‘burner’ and in just a minute or two was leveling off at 33,000 feet. A minute and nineteen seconds are all this fantastic bird requires to accelerate from .9 to Mach 2, and at a little over Mach 2 I’m pulling up into the 85 degree angle predicted to take me up to a hundred thousand feet or so.

I soon discovered that it was not impossible to bend my arms and legs and get back on the controls. But with the engine dead the throttle was useless and the air was so thin it render the stick a meaningless protuberance in the cockpit. With no control over anything for the foreseeable future, I relaxed to enjoy the ride. At what Edwards would later confirm as “over a hundred thousand feet” (perhaps generously so), the bird had reached it apex and coasted over the top. Still in an insane nose high attitude, the thing was now descending and accelerating tail first. There was little to do but marvel at the ride down. Take a moment to understand the situation; this is going to take a long time. We’re falling at maybe 10,000 feet per minute and we have something like a hundred thousand feet to go. Two or three minutes go by before the nose points down. Five or six minutes pass as I fall toward the desert. Five or six minutes! It seemed a lot longer then, but finally air has entered the intakes and the engine has slowly come up to twenty or thirty percent. From here it’s a simply a matter to wait for the dense air down around twenty five thousand, bring the throttle around the horn and light off. The engine comes to life as well as ever and we head back to George. I’m still fat on fuel but the pressure suit and the desire to rag on the two architects of my experience take me to the pattern and landing. As I reach the pits and shut down the crew chief is grinning as he runs up the ladder. He knows the plot and asks if I’ll need to have the suit cleaned out. “Very funny” I retort. I suppose most pilots plan for the fact that the engine will quit, that they’ll loose pressurization, that the suit will suddenly inflate and that their arms and legs will shoot out; but I for one wouldn’t trade the surprise and joy of the way that flight went for anything. Sure it’s obvious that the engine would give up when it ran out of air, but sometimes passion and joy obscure the obvious.

I soon discovered that it was not impossible to bend my arms and legs and get back on the controls. But with the engine dead the throttle was useless and the air was so thin it render the stick a meaningless protuberance in the cockpit. With no control over anything for the foreseeable future, I relaxed to enjoy the ride. At what Edwards would later confirm as “over a hundred thousand feet” (perhaps generously so), the bird had reached it apex and coasted over the top. Still in an insane nose high attitude, the thing was now descending and accelerating tail first. There was little to do but marvel at the ride down. Take a moment to understand the situation; this is going to take a long time. We’re falling at maybe 10,000 feet per minute and we have something like a hundred thousand feet to go. Two or three minutes go by before the nose points down. Five or six minutes pass as I fall toward the desert. Five or six minutes! It seemed a lot longer then, but finally air has entered the intakes and the engine has slowly come up to twenty or thirty percent. From here it’s a simply a matter to wait for the dense air down around twenty five thousand, bring the throttle around the horn and light off. The engine comes to life as well as ever and we head back to George. I’m still fat on fuel but the pressure suit and the desire to rag on the two architects of my experience take me to the pattern and landing. As I reach the pits and shut down the crew chief is grinning as he runs up the ladder. He knows the plot and asks if I’ll need to have the suit cleaned out. “Very funny” I retort. I suppose most pilots plan for the fact that the engine will quit, that they’ll loose pressurization, that the suit will suddenly inflate and that their arms and legs will shoot out; but I for one wouldn’t trade the surprise and joy of the way that flight went for anything. Sure it’s obvious that the engine would give up when it ran out of air, but sometimes passion and joy obscure the obvious.